Let me start by saying this: I have never heard an Irish person say ‘Top o’ the morning to you’. Or ‘Begorrah’. And the only time I’ve heard ‘To be sure, to be sure, to be sure’ was a tour guide explaining why Irish whiskey is the only variety to be distilled three times instead of the usual two. Either they are are all urban legends or Irish language has moved on since they became clichés in the wider world.

Irish English (as opposed to Gaelic, which we’ll get to shortly) comes in several options. There’s your fairly normal model where someone speaks more or less like I do except for with an Irish accent. There’s your almost poetical option, as spoken by our friendly local handyman Tom, who I could listen to all day. There’s your very colourful option, probably where the urban legend phrases come from, jam-packed with idiom and verve and life. And then there’s the one where I can’t understand a word that’s said no matter how many times it’s repeated which is why I can’t leave the house for a week when Gerry the plumber phones because I have no idea what he might have been trying to tell me and it would be rude to be out if he turns up.

Irish people can tell you which part of the country another Irish person is from by their regional accent. I’m never going to be able to do that except for those from Northern Ireland, and I’m sure there are local nuances there too that I’ve missed entirely. In Northern Ireland ‘now’ rhymes with ‘rye’ and ‘grace’ has about five syllables. As a person from a country with a very similar size and population but, at least in English, no regional speech variation whatsoever except for the slight Scottish influence down Gore way, I find this interesting. I assume it’s because Ireland was populated thousands of years earlier than NZ and by people groups with more diverse origins so each region in Ireland developed as its own small settlement rather than as a cohesive whole. Belfast is an easy ninety minute drive from Dublin – the distance from Auckland to Hamilton – yet as soon as someone opens their mouth there’s no mistaking which they grew up in.

Irish language (Gaeilge) is the first official language of the Republic and is compulsory in school here from go to woah. In theory all adults should be more or less fluent. In practice I don’t think this is the case. I certainly don’t hear it around. You do, I believe, need to be proficient in it to some particular standard to be employed in any public service capacity. If I wanted to be employed as a teacher here I’d have to learn Irish first. It doesn’t seem to get much use at all in the general population, however. There are a couple of small villages where it’s spoken as a first language and there’s an area along the West Coast called the Gaeltacht (pronunciation: your guess is as good as mine) where it’s more common but in general it’s regarded, according to a recent survey I read, as being far more important as a symbol of national identity than for any practical purpose. It was the predominant language through Irish history until the Elizabethan British tried to wipe it out in the 1700s. Its usage declined sharply after the famines, which hit the Irish-speaking rural areas particularly hard. By the end of the 19th century only 15% of Irish people were using it. In recent years all kinds of efforts have been made to try and bring it back to life. Sound familiar?

At school Amy and Daniel have exemptions from learning Irish. There are strict criteria for this and they fit the clause that excuses children who have been educated up to age 11 in other countries. You can also be exempted if you have severe learning disabilities or if you have arrived in Ireland unable to speak English, in which case you can choose to learn either English or Irish (and I bet Irish doesn’t get a lot of takers from that group). I would have been quite happy for Daniel and Amy to give it a go but all the others of their age have been at it for eight or nine years so it’s a bit of a leap.

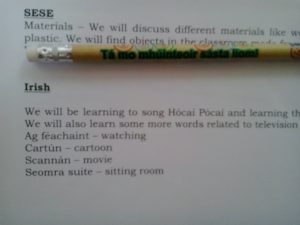

Cassia, who’s now attained the status of Senior Infant, comes home singing nursery rhymes and playing Simon Says in Irish. It’s very cute. I don’t understand a word. They could be teaching her Gerry the plumber’s brand of Irish English for all I know. But she likes it. She’s starting on simple sentences now and can say ‘I like talking in Irish’. If you’re trying to rejuvenate a language you might as well start the brain-washing early, I suppose.

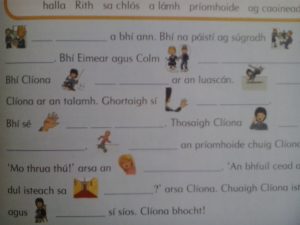

Noah, though, he’s picking it up like nobody’s business. He can read aloud all the work in his little exercise book (they have these tiny books that they call ‘copies’) and is recognising words from road signs. He can do all sorts of sentences, mostly of the ‘I like cake’ variety. It’s a shame in a way that it’s not likely to have any real-world application after the next year or so, but as we all know, learning a second language early is good for the brain development regardless. Neural pathways and all that.

Anyway, on the off-chance that you’re in the neighbourhood and decide to drop into Ireland for a cup of tea, I thought I’d give you some basic vocabulary to get you started.

Yoke: a thingymajig. You know, something small and useful that you don’t know the name of, if it even has one. As in, ‘Just pass me that yoke and I’ll have it fixed in no time.’

Craic: fun. A Gaelic word, pronounced ‘crack’. As in, ‘Ah, she’s great craic, that one’. Also used as a greeting: ‘What’s the craic?’

Fáilte: welcome. Also a brand of toilet paper. Go figure.

Gas: funny. ‘You’re a gas woman, so you are’. One of the dads at school, watching Cassia playing with his son in her usual flamboyant manner, said to me, ‘She’s gas isn’t she?’ Which is one way of putting it.

Ye: the plural of ‘you’, and gosh isn’t it handy? You know how you quite often want to say ‘youse’ to make your meaning clear, especially when speaking to kids (‘You clean this up now! No, don’t disappear, I didn’t mean just her, I meant all of youse!‘), but you can’t quite bring yourself to? Fret no more. In fact, the Irish spinkle around plurals of ‘you’ with what used to be called gay abandon. ‘Yiz’, ‘yiz all’ and ‘yizzers’ are all acceptable.

The parents’ room notice board inviting volunteers for the next bus trip, Irish fashion. In a school.

So: comes at the end of a sentence to show you’ve decided on something. ‘I’ll see you at seven, so’, or ‘I’ll put you down for three tickets, so’.

After: sort of a crutch that verbs lean on. ‘I’m just after cleaning that floor and look at your shoes!’ ‘I’m after getting completely soaked on the way home’. ‘They’re giving out free fruit at school and aren’t I just after buying some!’

Giving out to: having a go at. ‘I’m always giving out to her for leaving the immersion on’. ‘Ah, I’d better go or she’ll be giving out to me for being late’. Often combined with ‘after’, as in ‘Don’t you be after giving out to her now!’ In fact you could aim for the hat-trick and chuck a ‘so’ on there too: ‘I told him he could have that last piece of cake so don’t you be after giving out to him, so!’

Lookit: similar to ‘look’. ‘Ah, lookit, I’ll do it as soon as I can’.

The immersion: a symbol of Irish national identity as integral as Gaeilge, masquerading as a water heater. We are still not even going there about the hot water unless you want me to be giving out to you until bedtime.

It’s more Irish than Guinness, leprechauns and St Patrick – making a sign to remind yourself before you let it blow the roof of the house entirely.

Is it?: In Kiwiland if we want to use an interrogative at the end of a sentence we pick the one that matches whatever we’ve just said. We might say ‘You haven’t seen that movie yet, have you?’ or ‘You wanted the green one, didn’t you?’ But the Irish don’t seem to want to get too fancy and so ‘Is it?’ is the all-purpose go-to. So you get things like, ‘You want the ten 0’clock appointment, is it?’ or ‘You’re wanting to renew these books, is it?’ It keeps things simple, once you get used to it.

Ma/Da/Grand-da: Mum, Dad and Grandad.

Mammy: Mummy. I hear adults using this more than children, as in ‘We need to get packed up, kids, all the mammies will be waiting.’

Tree: three. Dubliners will not believe you when you try to convince them of this but they cannot pronounce ‘th’. ‘I think there are three’ turns into ‘I t’ink dere’re t’ree.’ They just can’t hear themselves doing it.

Haitch: ‘h’.

Dote/dotey: cute. As in ‘She’s a little dote’ or ‘Wouldn’t that dress look dotey on her?’

Thanks a mill: Thanks a million. Everyone says it. All the time.

Sure and…: Something to put at the start of a sentence when you feel like it. ‘Sure and you’ll be grand’. ‘Sure and I forgot about it entirely.’

Press: cupboard. The hot press is the hot water cupboard. Why? No idea.

The guards: policeman. The national police force is called Garda Síochána na hÉireann, the Guardians of the Peace of Ireland. Policemen are Gardai in the plural and Garda in the singular but referred to as ‘the guards’ in general conversation. It comes up a lot in graffiti on the walls of the inner-city estates also.

Fair play to you: an expression of respect, a compliment on a job well done. When Amy hurtled into the world under a crucifix and with ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ playing on the radio (coincidence? I think not. They probably have it on loop in the labour ward) the midwife who’d watched me go from three to ten centimetres in under an hour and completely lose my mind as a result caught her and said ‘Fair play to you’. And it meant something to me, hearing that. But you can use it under less extreme circumstances also.

Eejit: idiot. ‘Ah, you forgot your keys again, ya big eejit’.

Shite/feck: lovely handy non-offensive words you can just put in anywhere.

I said back there somewhere that if I wanted to teach here I’d have to learn Irish first. Frankly it would be easier just to retrain as something else – a brain surgeon, maybe, or a rocket scientist. If they were giving out medals for the world’s most non-phonetic language Irish would be up there in the top five along with Welsh and anything in a non-Roman alphabet. Off the top of my head, for example, I can think of three different ways to form the ‘v’ sound and none involve using a ‘v’. You can use ‘mh’ as in Niamh (Neve). You could opt for ‘bh’ as in Siobhan (Shivorn). Or for extra oomph you could go for ‘dhbh’ as in Maedhbh (Mave). For the life of me I can’t hear any difference in the pronunciation of the ‘v’ sounds in those three words that would warrant three different spellings – and for all I know there are many, many more – which is why I’m thinking that rocket science would be the easy option.

Then there’s the matter of pronouncing names. A very common boy’s name here at the moment is Oisín (Osheen), which I think I’ve got the hang of because Cassia talks about the ones in her class quite a bit. Then there’s Grainne (Grawnya), Tadgh (Tiger without the ‘r’), Aoife (Eefa), Aine (Onya), Fionnuala (Finoola) and Padraig (Pawrick). These are the easy ones. There’s a girl at the high school called Saobhraidh, which even Google doesn’t have a pronunciation for. It could be one of those makey-uppy names like Jakxsyn or Madysyn and how would you know? See what I mean about non-phonetic? There are three children next door who play with Cassia and Noah. A few days ago I wrote out invitations for them to Cassia’s birthday party and the possibility of being caught out by unexpected spelling came into play. Aidan – can’t go too far wrong, I’m thinking. Tiernan – I’ve seen it written on their mail (no, I wasn’t stalking, it was delivered to the wrong house). And Keelin. It sounds straight-forward but that ending could be i-n, e-n, a-n, y-n or, knowing the Irish, gptxw. I went with i-n thinking that’s what I would choose if she were mine. And now, having delivered the invites, I’ve looked it up and guess what? It’s Caoilfhionn.

For feck’s sake.

Awesome as always! Having tried to get my head around Welsh (my maternal grandparents were Welsh), I can appreciate some of the challenges!!! Thanks for taking the time to share, your writing is a real highlight of my week😀❤️😀

lol… that brings back memories of trying to type minutes while working in Ireland. I was hopeless.. didn’t understand a word! Why they kept me I don’t know, maybe because they liked my accent 😉 I did however know the words ‘eejit’ and ‘shite’ though…..

I love your blogs Mel, thanks for sharing!