And how things have changed.

This is Phoenix Park in 1979, when the Pope last visited Ireland:

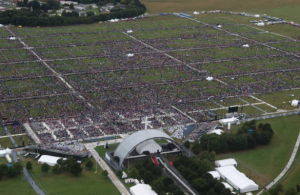

And this is Phoenix Park in 2018:

See the difference there? The top picture shows what a crowd of 1.25 million looks like. The bottom picture shows a crowd of 130,000. There’s plenty of empty space there, because half a million free tickets were snapped up, but less than a third of the expected number turned up. Perhaps some people were put off by the weather forecast, although it turned out a nice day. Maybe some couldn’t manage the long walk from the designated drop-off areas. Certainly anti-Pope protest groups were bagsying as many tickets as they could get their hands on with no intention of coming.

Back in 1979, enthusiasm was such that some enterprising soul invented and sold Popescopes, your own personal periscope to help you get a better view:

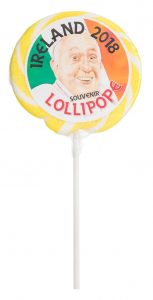

Popescopes were not available this time around – possibly because people don’t go for big hair in quite the same way nowadays, so that extra foot isn’t such a big deal – but for the bargain price of just €1.50 you could have this beautiful commemorative lollipop instead:

and who doesn’t love a lollipop?

I’ll tell you who’s not feeling the love at the moment though, and that’s the leadership of the Catholic Church. In 1979 2.5 million people around Ireland went out of their way to see Pope John Paul II, from a population of 3.4 million. Last month, the combined total of pilgrims (you’re not an audience if it’s the Pope, you’re pilgrims) who attended the masses was just 175,000 from a population which has risen to 4.7 million.

It wasn’t that everyone else was ignoring the Pope though. No, no no no. There were plenty of people out looking for his attention.

There was this large crowd, wanting the church to admit to, apologise for and make a serious attempt to redress the large-scale clerical abuse of children and the institutional cover-ups of said abuse – oh, and to stop doing it.

The march ended up at the site of the last Magdalene Laundry which closed in 1996, which isn’t all that long ago really.

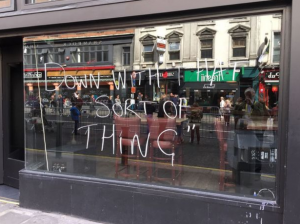

Then there were these guys, expressing the novel idea that perhaps a church without abuse would be a good thing.

There was the group who made the already beautiful ha’penny bridge much brighter to publicise their trio of requests: that the clerical abuse scandal be properly acknowledged and dealt with, that women be allowed leadership positions within the Catholic church, and that the church could also please be a bit nicer and more welcoming to the LGBTI community.

It all sounds so reasonable when you put it like that.

The other side of the ha’penny bridge featured a quiet memorial to the victims of abuse by clergy:

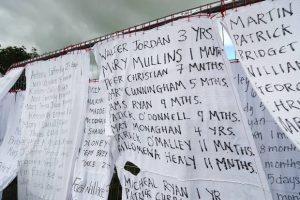

and over in Tuam, just a short hop from Knock, the venue for the first Papal mass of the visit, things got seriously real:

I have mentioned the mother and baby home run by the Order of the Bon Secours Sisters in Tuam before and we don’t need the gory details again. On the morning of the nearby Papal mass a silent vigil was held there in memory of the 796 tiny souls whose remains are still on site in a septic tank. Their names were written on bed sheets and they were represented by tiny pairs of baby shoes as people gathered holding cards with the names of the mothers and babies who never left the home on them.

For 175,000 pilgrims this Papal visit was a chance to see an icon, a hero perhaps, God’s chosen representative on Earth. For most of the rest of Ireland, it seems, it fell somewhere along the spectrum from ‘of no interest at all’ to ‘the best chance we’re going to get to be heard by someone with power’ with a smattering of ‘couldn’t they think of anything better to do with €32 million?’ mixed in.

I’m sure the €32 million could have been better spent, because here’s the thing. Until the church cleans house thoroughly, until it says what 4.7 million (minus 175,000, I guess) people need to hear, there’s no point in it saying anything at all, because nobody’s prepared to listen. It seems to me that the low turnout to see the Pope, the vote for marriage equality three years ago, the recent abortion referendum result, the fuss over the ownership of the new maternity hospital and the early but audible murmurings about removing schools from church control are symptoms of a popular belief that the church and its teachings have lost all respect and how can it expect otherwise when it is visibly dragging its feet on the issues of bringing known criminals to justice and of doing everything possible to repair the harm done by so many of its members? Who’s going to listen to lessons about love and kindness and morality and integrity from a bunch of people who have been failing spectacularly in all those areas for decades and who are not yet fronting up and doing what it takes to start a process of healing and reconciliation?

In individual churches across Ireland priests who are good men are surely doing the work of God among their congregations and in their communities. There is still a living faith. There is plenty of good there. There must be. It’s a shame that’s all overshadowed, and the sad thing is it probably doesn’t need to be. It doesn’t have to be past the point of no return.

The Pope did make some apologies, but apologies aren’t enough. Every priest and every nun who committed a crime needs to be held to account for it through the civil justice system. Every priest and every nun who knew that abuse was happening and ignored or enabled it needs to be held to account. That’s a tall order. Three of the cardinals who were supposed to be accompanying Pope Francis to Ireland pulled out – or were pulled out – because they have all been accused of knowingly sheltering abusers. Maybe there won’t be many high-ranking Catholics left. Maybe that wouldn’t be a bad thing.

Then, they need to pay their outstanding torture bills. It seems obvious.

They would also need to throw their considerable resources behind an all-out, balls-to-the-wall effort to repair the damage that was done by the decades of abuse, to survivors and families of those who didn’t survive. They would locate all the babies who were sold and adopted without consent from the mother and baby homes and give families the opportunity to be reunited. They would unseal all birth, adoption and death records that are being withheld. They would provide any and all financial support necessary to try to repair the physical and emotional damage done to abuse victims, mothers whose children were taken, children whose mothers were taken, and symphysiotomy patients. They would dig up the grounds of all the former homes, laundries and industrial schools where people are buried, identify them all and give them decent dignified re-burials. They would go through all their records, work out the exact amount of money that was made from the baby trafficking, and give it all back.

They would give serious thought to the idea that if the church got rid of the requirement that priests be celibate for life, and accepted women as having valuable contributions to make in leadership, the whole enterprise might become far more healthy and functional and relevant.

They would be humble. They would prioritise serving the people of Ireland through the healing process rather than controlling them. They would become fully transparent.

It would be a massive job. It would take years and cost plenty. But it could be done. It’s not impossible. Maybe then there could be some forgiveness, some peace for the people still suffering. Maybe the next Pope’s visit could be about God, about all the good things that Christianity has to offer. Maybe the focus could be on what he does say rather than what he doesn’t, on hope not shame. We could all be out there with our Popescopes and our lollipopes to cheer on God’s main man as he does his thing. By the grace of God – and the many people now rising up to demand better – anything is possible.