This morning Daniel was still asleep when his brother and sister left on the school bus and his father left for work. I went and prodded him into semi-wakefulness and before his eyes were fully open he started whingeing about having to go to school. He got up and grumbled and moaned his way around his morning jobs and then just started begging. School’s boring. He hates it. They have spelling tests on Fridays. Apart from lunchtime there’s nothing fun at all. He’s one of only three poor deprived kids in the class who haven’t had a day off all year. Some of them have been on two-week holidays overseas during term time. What’s one day off going to matter? It’s not like the cops are going to turn up and find him at home instead of school.

For me this is a very unwelcome blast from the past. We have suffered through years of this on a daily basis, sometimes with the added fun of Josh having to carry him kicking and screaming and physically strap him into the car. There have been many, many times when I’ve watched with a breaking heart and wondered what we’re doing to him and why, exactly. We have certainly considered other options, often, but none of them have been right at the time either.

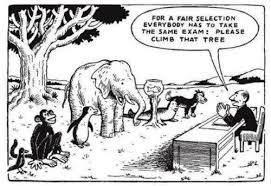

Daniel has dysgraphia which means that he loves Lego and computer games but hates reading and writing. He has a learning style called 3D visual-spatial which schools haven’t really discovered yet. He’s also borderline hyperactive so that if whatever he’s supposed to be doing at school isn’t quite working for him he’ll find some other way to entertain himself rather than self-consciously blending into the background. Daniel does not blend. He scores in the high 90s on the percentile charts in many elements of the intelligence test so he cannot be fobbed off with a colouring-in sheet and a picture book.

As a teacher a child like this is either your worst nightmare or an exciting, if challenging, opportunity. For the last year and a half we’ve been lucky enough to have had teachers for Daniel who see potential and value in him and who realise that the irritating class clownism and constant activity are symptoms of an environment that’s not a perfect match for his learning style, rather than being the sum total of his classroom ability. It’s been a huge relief to us and a far less miserable experience for Daniel and the crying and pleading in the mornings has largely disappeared.

Here’s the sad thing about Daniel: he wasn’t always this way. As a pre-schooler he was the most co-operative, charming, easy-going bundle of fun around. He was active, yes, but always pleasant and positive and bright-eyed and bushy-tailed. Kindy had no complaints about him and nor did anyone else. He started school with a wonderfully competent and experienced new entrant teacher and the future looked rosy.

Now I’m a trained teacher and a parent of many small people on the road to literacy and numeracy and here’s my professional opinion, for what it’s worth. We do not need to spend $300 million on bringing class sizes down. We do not need more teachers. We do not need more managers in schools or any of the other things that I’ve seen waved around as election promises with big price tags. What we need, what we desperately need, is for all teachers to be trained to recognise children with dyslexia, dyspraxia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia and all the other dys-es very early; for there to be a whole army of people trained to work with these children effectively; and for there to be some sort of pre-school screening programme so that ideally these children never have to arrive at school only to be put into the situation that Daniel found himself in for years until we, the parents, against the principal’s advice and at our own cost, did something about it. And yes, this is a big-budget deal.

Because here’s what happened to Daniel. He got to school, all keen and ready. Then he found that when the teacher taught he didn’t learn. For several years he didn’t learn and all that time people kept telling him, you need to try harder. You need to concentrate better. Sit still! You need to be spending more time on homework. So he did all those things and when he still didn’t learn he was told to do them some more. And some more. He was kept in at lunchtime to finish work he hadn’t finished in school time. He was given more spelling words to learn so he wouldn’t fall so far behind because he hadn’t managed to learn the last lot yet. And our school has this wonderful policy – with research to back it up, no doubt – of putting little photos of all the kids’ faces against the levels they’re at for every subject on the classroom walls. So all this time Daniel knew that every parent, teacher and child could always see at a glance that he was on spelling list C even though he was in year 4 and everyone else was on M or S or W. And just try telling the teacher that you don’t want that little photo on the wall. It motivates them to do better, apparently. When you ask, if that was going to work don’t you think he’d be further along than set C after four years at school, they say well, if he would just concentrate harder and if you were doing more homework with him.

A few nights ago we had parent interviews and the picture I get from the teacher is this: Daniel is doing fine for his age in most things and very well in some. Spelling is a dead duck and anything that has to be filtered through the medium of writing suffers but he has lots of good things going on. We are saving up to get him an iPad with a word processing programme said to be ideal for this type of thing and, once the obstacles of spelling and handwriting are bypassed, miracles will follow.

But that’s not how Daniel sees himself. No, sir. Daniel thinks he’s dumb. He believes he won’t be able to do it anyway so what’s the point in trying. He knows he’s never going to get attention for his achievements at school so he makes sure he’s not overlooked by use of constant smart-arse comments and an often mis-timed sense of humour. His first few years of school provided constant failure and frustration for which he could see no reason. And now he’s more handicapped than he was before we had diagnoses for his various quirks because it’s his attitude and his self-belief that are wrecked, not his brain. And although he’s far better off now thanks to his current teacher, I do not know if he can be fixed. We won’t be getting back the sweet, happy little boy we sent off to school five years ago. I have grief to work through there.

Depending on whose statistics you believe between 6 and 10% of people have one or other of these dys-things going on. Teachers are not trained to pick it up and if parents suspect it and want it assessed there is no facility for this to be done within the school system. You have to do it privately and it costs an arm and a leg. When I first mentioned the possibility to the principal she said, ‘Oh, dyslexia. Yes, we had a child with that here a few years ago’. No, lady, in a school of 300 you have somewhere between 20 and 30 children with it right now, and every single one of them is struggling and miserable, and a fair few will be creating behaviour problems to deal with their boredom and frustration, as Daniel did.

This is why we do not need to spend hundreds of millions on extra teachers to get classroom sizes down a bit. If every child with one of these processing disorders was picked up before or at school entry and was taught by someone who knows what they’re doing we could increase achievement and participation as well as eliminate most of the time-consuming and distracting bad behaviour from classrooms. Class size is a red herring. It doesn’t matter. What matters is how many children within the class are taking up disproportionate amounts of the teacher’s time and energy. Most children who do so are not inherently bad or naughty; in junior classes they’re children who want to do well and be ‘good’ but who can’t, for whatever reason, engage fully with the class programme. If you have two or three Daniels in every class, which statistically you will, and you have parents who may not have the knowledge and resources that we did to deal with it themselves, you’ve got a problem which is only going to get worse as those Daniels get older and further behind and their attitudes of uselessness become entrenched. It’s also, of course, a huge waste of potential. Like Daniel these kids tend to be bright and after years of failing to learn and being told it’s their own fault all that ability and promise is going to be lost. If the government has a spare $300 million burning a hole in their pocket then this is where it needs to be.

Ultimately I know that Daniel gains more from school than he loses, whether he sees it that way or not, which is why we persevere. But it shouldn’t be something we have to balance up; he shouldn’t be losing anything by going to school. He shouldn’t have to lose his self-belief and his joy in learning and we shouldn’t have to lose the lovely little boy that he used to be. The enduring lesson we’ve learned as parents is that if we believe that something is right or wrong for him and the teacher and/or principal disagrees we need to follow our own instincts. A lot of misery could have been avoided if we hadn’t believed several years’ worth of teachers when they said that he was fine, that there were no underlying problems and that we couldn’t possibly know what we were talking about. Which is why I’m so torn when I have to bribe him with a treat after school to get his defeated shoulders and sad face into the car in the morning. How can I expect him to trust that adults know what’s best for him when between us and school we’ve spent almost half his life putting him through the soul-destroying daily grind of forcing him to jump through hoops that he can’t even see and then blaming him for not trying hard enough when he misses again?